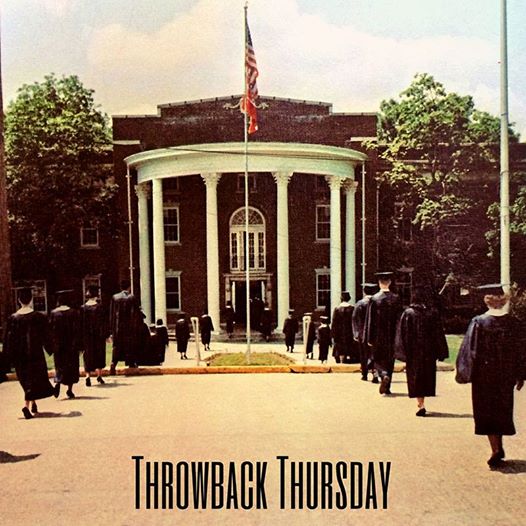

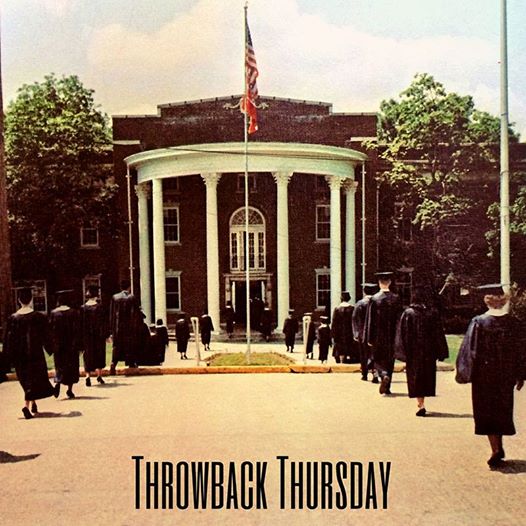

[Auditorium at Mississippi's Hinds County Junior College in 1968 on a different occasion.]

This Is For Bobby

Just

after sunrise the morning Robert F. Kennedy was killed overnight in Los Angeles, I was

standing in line outdoors with a few hundred other 16- to 17-year-old boys at

Magnolia Boys State. I was one of many from across the state selected as a future leader of Mississippi that year attending the annual

leadership camp sponsored by the American Legion.

The camp was held on the campus of Hinds County Junior College near Jackson, an overgrown plantation of a town of the Old Confederacy that was still to that day, and remains, the center of gravity of a violent hate and seething resentment, perhaps to forever proudly carry the contagious germ of evil from which issue the original sins of slavery, war, and genocide.

We were hearing the usual instructions for the day, the last day of Boys State,

when one of the adults in charge announced that RFK had been assassinated only hours

earlier. There were at most one and a

half seconds of silence, the calm before the storm, before a spontaneous

combustion of gathered hate ignited a cacophony of screamings for joy and delirious cheering, raucous,

loud, and utterly unrestrained, punctuated by whooping rebel yells, that lasted a minute

or two, though seemed much longer.

Not a single adult in attendance tried to quell the sad mad disturbance by the

handpicked future leaders of the state, nor said anything about it once it had subsided

nor anytime afterward. For me, it felt

like being a not-yet identified potential next victim among a mob of savage slavering

jackals rolling with snarling abandon in the bloody corpse of its kill, a scrum

of dumb and scum.

It was mortifying, dismaying, and distressing, a vivid moment I will always

remember clearly. I so wanted to say or

do something but was taken aback by shock and alarm.

Right after the morning instructions were over, I sought out one of the

college-age camp counselors, not one I knew but someone I hoped might could be

sympathetic. I asked him for help, and

this is what he managed to accomplish at my urging, which seemed would have

been next to impossible on such short order.

1) He procured a spot for me in that night's Magnolia Boys State closing

ceremonies to take place in the campus auditorium, a few moments onstage to

myself. 2) He located and bought the

sheet music for a specific song. 3) He

found a fellow counselor to play the song on piano. 4) He located a piano, likely in the

auditorium complex, and had it brought onstage.

Then without an introduction and with the accompanist seated at the piano in

that darkened auditorium, I walked to the center front of the stage to the

microphone stand, still burning if not seething against the tawdry spectacle of

early morning, and without any comment myself sang "The Impossible Dream"

to a captive audience of by far mostly misbegotten racist hateful youth.

It wasn't enough. I didn't say, "This

is for Bobby". I didn't 'say'

anything about what had happened. I just

did what I could and was too afraid, angry, or both to do more. It's probably the most heroic thing I'll ever

do, which if anything may point out that I could have done a lot more or better

with my life, but I'm glad somebody did something.

And,

yes, it was for Bobby.

And it was for

Medgar Evers, killed five years earlier at his home, also in Jackson.

And it was for the three civil rights workers,

James Andrew Cheney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael "Mickey" Schwerner, killed

four years earlier 80 miles northeast of Jackson outside Philadelphia.

And it was for the four Birmingham girls

killed five years earlier in the Sunday bombing of their 16th Street Baptist

Church, for God's sake, Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley,

Carole Robertson, and Addie Mae Collins, because they happened to live their innocent young lives in Birmingham, a city that was not a city, because a city is supposed to be civilized, and instead was a colonial outpost of hate and vile murder, slavery and Jim Crow's self-entitled legacy; and 238 miles from Jackson.

And it was for Martin Luther King, Jr. killed only two months earlier

just across the Tennessee state line in Memphis, a distance of 210 miles from Jackson.

And it was for Phillip Lafayette Gibbs, a college junior, and James Earl Green, 17, a high school senior, who were gunned down by Jackson police on the Jackson State College campus two years later, in 1970, for demonstrating against war with hundreds of others, all unarmed.

And it was for Bud Strong of Biloxi, a sweet and

harmless mentally retarded African-American man, and another victim of a Jim Crow death squad, who was kidnapped and murdered

in 1960, and whose body was left in front of an historical Biloxi

tourist site named "Beauvoir", which was Confederacy President

Jefferson Davis' estate across from the beach, a beautiful site covered with huge oaks and over which a

huge Confederate battle flag is flown.

This

hate crime occurred in the direct aftermath of a terrifying nighttime white

race riot of shootings, firebombing, and other violent attacks against "Back-of-Town", Biloxi's

black community, in retaliation for a Wade-In demonstration earlier that day to

desegregate the beach. Biloxi is 167 miles from Jackson.

And it was for Malcolm Jackson, another young

African-American man from Biloxi, who was beaten to death

in 1960 in the Wade-In riot's aftermath also, by Pascagoula, Mississippi police. Pascagoula is 20 miles from Biloxi and 165 miles from Jackson.

And it was for Dr. Gilbert R. Mason, a Biloxi physician who

as an indefatigably courageous physician, healer, leader, local NAACP

president, former Boy Scout and Boy Scout troop leader, and upright activist

who did so much for so long to help right the ungodly wrongs in my hometown, state,

and country. Dr. Mason, against all odds

and attempts, was able to live a long full life, and I wish to God I'd known

him. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=97568717